Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/308309765

YouTube: https://youtu.be/xpVvTuxP1XA

Welcome to Kerbalism! I’m your host, Aubrey Goodman. In this episode, we deploy two relays to solar orbit to become the backbone of our solar system communications relay network.

Before we can expand our horizons to visit other planets in the solar system, we need to have some infrastructure. Satellites sent to moons only need to communicate back to their planetary base. If we sent a satellite to another planet, we would need to make sure it has a very powerful radio to reach our home base. Also, as planets move around the solar system, the distance between them changes. In some situations, planets might find themselves on opposite sides of the star.

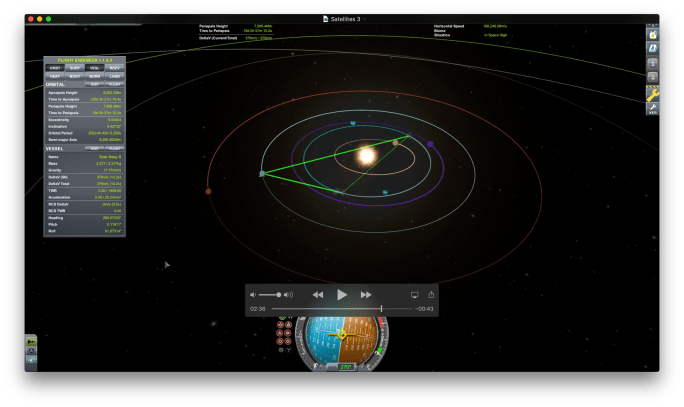

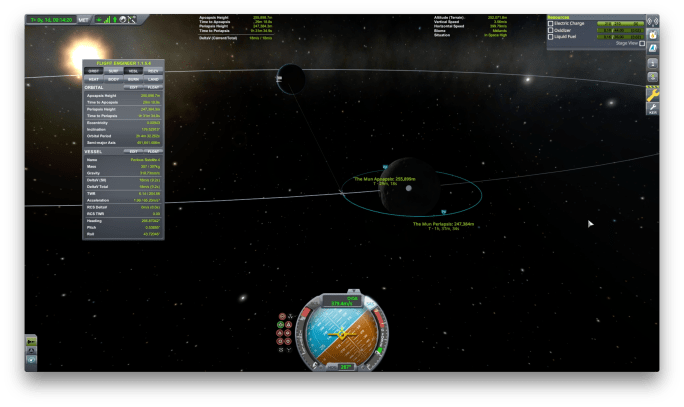

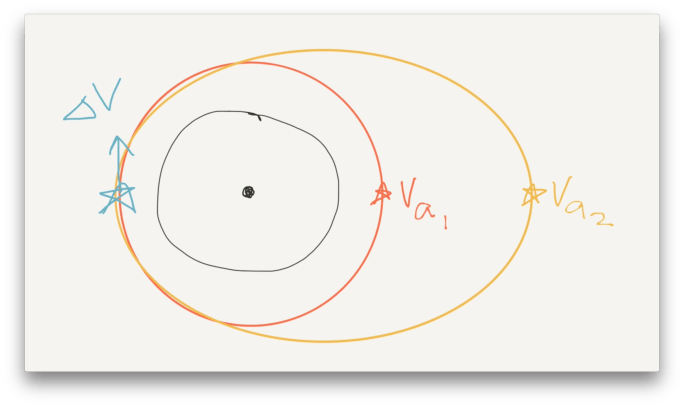

If we introduce a relay network in solar orbit, we can support a wider range of missions. Kerbin orbits around its star at 13.6 million kilometers. By placing a pair of relays in solar orbit at 8 million kilometers, the relays themselves are never more than 16 million kilometers apart, nor more than 16 million kilometers from Kerbin. This way, anything within range of a relay will be able to communicate with home base.

For orbital missions, such as placing satellites in orbit of other planets in the system, having a solar relay network is vital to maintaining connection with your probes. This will reduce payload antenna requirements and thus reduce costs, enabling more missions over time.

Observant viewers will note the two-node approach suffers the problem of having the star directly in the line-of-sight path between the relays. Using a three-node approach would eliminate the line-of-sight problem, at the cost of one extra relay. Also, positioning the relay itself is a very slow process, and making adjustments along the way would use too much fuel. Like so many things in space, it’s important to get it right the first time.

In this case, we settle for having two relays in circular solar orbits, and not quite exactly opposite each other. This gives us coverage for missions to all inner planets. The natural evolution of our relay network is to send smaller relays to each planet. This enables reduced cost missions with smaller radio equipment. If the probe only needs to communicate with the nearest relay network node, we can use the same equipment we used for lunar satellites.

So that’s all for relays. Now that we have the basis of our relay network, we can begin to discover more things about our solar system. One way we do that is by building stations in orbit. So, in our next episode, we’ll discuss orbital stations around our planet. Stay tuned!

And thanks for watching Kerbalism!