Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/324381843

YouTube: https://youtu.be/1MprhkvcIaw

Welcome to Kerbalism! I’m your host, Aubrey Goodman. In this episode, we upgrade a manned surface station into a mining colony.

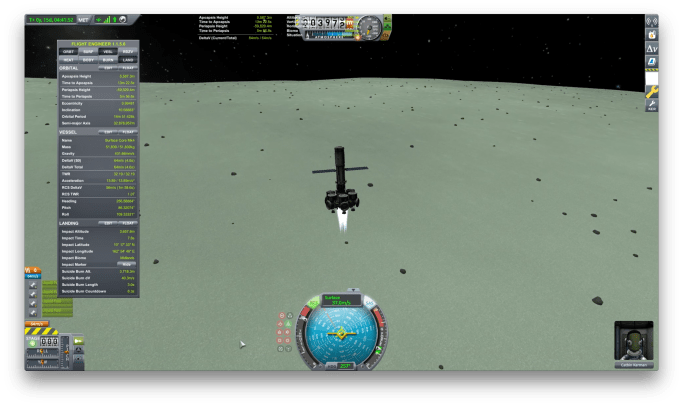

In our last episode, we landed a construction core on Minmus, ready to expand itself to support higher volume resource processing. Now, it’s time to grow our station into our first mining colony. We need a manned presence to enable ongoing mining operations, extracting resources from the surface.

With asteroids, there is a much smaller opportunity for resources. If the asteroid is only one thousand tons, we spend a lot of energy and time with finite benefit, equal to the mass of the asteroid. We must repeat this for each asteroid we wish to harvest. If the asteroids are small, we may use more resources capturing them than they yield from processing.

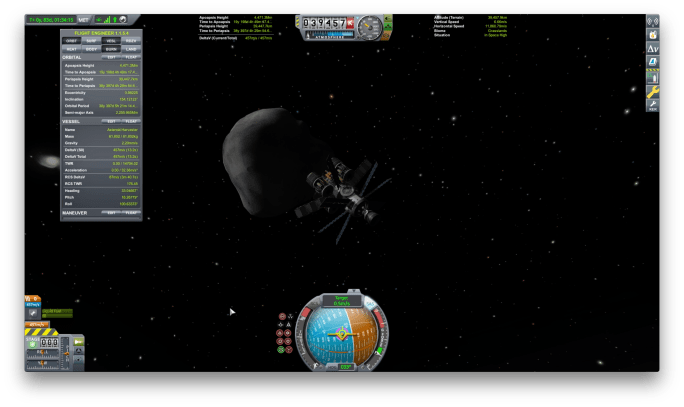

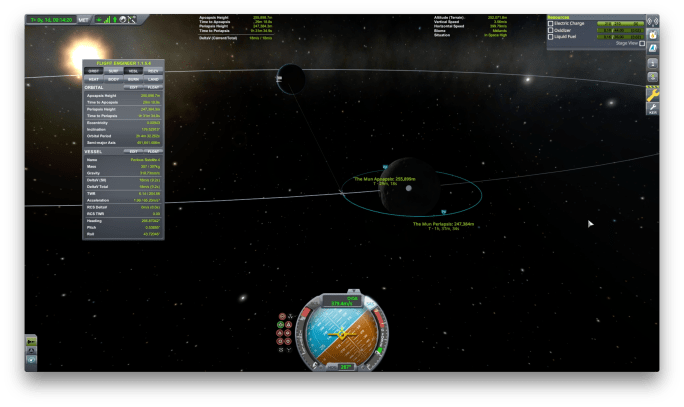

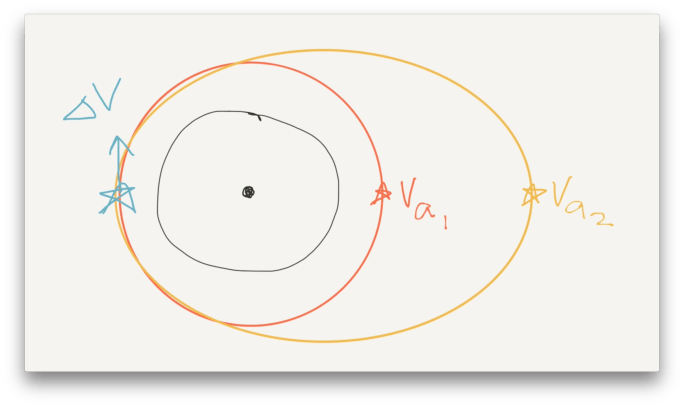

Moons are different. Resource abundance on the moon surface is effectively limitless, compared to the cache in the asteroid. Once we’re settled in at a good location, we can produce an arbitrary amount of fuel and send it back to orbit. We’ve chosen Minmus because its surface-to-orbit delta-v is very small. The cost of sending resources from the surface to orbit is much lower than Mun or Kerbin. From the surface of Minmus, we can launch into low planetary orbit for about one third the cost of launching from the planet directly.

The construction core is designed for expansion. The goal is to land the bare minimum mining gear and use it to build the rest on-site. Our station core has both radial and vertical expansion options. After we add processing components, we expand outward with more support struts with the same radial and vertical options. These become new expansion points and we repeat as needed.

Of course, expansion comes with its own challenges. Our first expansion of processing equipment was lost when it overheated and exploded. Fortunately, no other nearby parts were damaged. The expansion plan must include increased solar and thermal management. We also need to leave room for ships to land for refueling. These vessels will not be docking in the traditional sense. They simply land near the station and connect via fuel hose. The hoses are limited in length, so ships will need to land close to the hub and wait for colony crew to attach the hose before fuel transfer can begin. Once attached, the station can transfer stored fuel or make new fuel on-demand, until the ship’s reserves are full. Then, it’s simply a matter of detaching the fuel hose and blasting off to Minmus orbit to rendezvous with an orbital fuel station.

Using this technique, we can deliver fuel within our planetary system to support the needs of any ships traveling between the planet and its moons. As we expand to other planets, we create new mining colonies on moons as needed.

As always, thanks for watching Kerbalism!