Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/307753956

YouTube: https://youtu.be/qCvHz1n0qxU

Welcome to Kerbalism. I’m your host, Aubrey Goodman. In this episode, we’ll review the deployment of satellites to lunar orbit.

First, let’s expand to consider the nearest moon. It requires more deltaV to get there, and more still to stabilize in a circular orbit. The good news is our Kerbin orbital satellite is over designed for its task. Its first stage does almost all the work, and we have plenty of fuel left over in the second stage for transfer orbit burns.

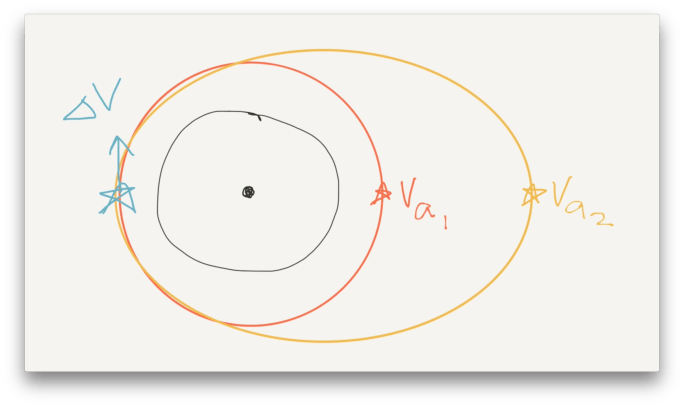

Once the craft is in planetary orbit, we need to perform two maneuvers to stabilize into orbit around Mun. If we do a really good job executing the maneuvers, we will settle into a circular orbit.

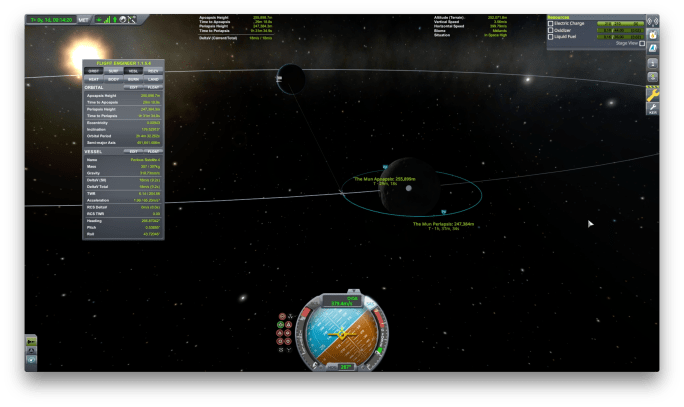

Orbital transfer between Kerbin and Mun can be done really at any time from a mostly equatorial orbit. This refers to the inclination of the orbital plane relative to the rotation of the body. Kerbin and Mun have very similar inclination, making it convenient to transfer between them. As we’ll find later, Kerbin’s other moon, Minmus, has a different inclination.

While a transfer can be made between Kerbin and Mun at any time, there are optimal points along the orbit where fuel use can be minimized, due to favorable alignment. Sometimes, we can save a huge amount of fuel simply by waiting for 20-30 mins.

Once we find a transfer orbit we like, with a destination periapsis at the desired altitude – that means the periapsis of the resulting orbit around Mun – once we find that periapsis, we can proceed with executing the maneuver at the appropriate time. Even perfect execution will result in slight misalignment with your designed objective. This is expected. If necessary, you can make corrections with RCS, but this is generally not required.

Now, after some time has passed your craft has traversed its path and is now approaching the periapsis of the destination orbit. You must burn retrograde until you slow down enough to stabilize into an elliptical orbit. Then, bring the apoapsis down to around the same altitude as the periapsis, resulting in a circular orbit.

Kerbin has a second moon, called Minmus. Its orbital inclination is about 6 degrees higher than Kerbin, so any craft headed there must also perform a maneuver to align its inclination. This is ideally done during orbital ascent, which reduces the inclination difference.

Our over designed satellite has enough fuel to enter stable orbits of both moons. But it also does very little. As we add capability to our satellite, the payload mass increases, and the first stage fuel requirements increase exponentially.

So that’s it for lunar satellites. In the next episode, we’ll focus on solar satellites; that is, satellites on an orbit similar to a planet. Those will lead us to a place where we will be able to establish a relay network of satellites that allows us to explore a wider part of the solar system. So stay tuned for that and much more!

And thanks for watching Kerbalism!